In the late evening hours of August 17, 1969, a catastrophic storm named Hurricane Camille slammed into the Gulf Coast. A Category 5 hurricane, with sustained winds of 175 mph and a storm surge of more than 24 feet, Camille devastated much of coastal Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana. More than 250 people lost their lives and damage was estimated at about $10 billion in 2019 dollars.

Decades later, scientists reviewing archived satellite and radar data learned that it was the second-most intense hurricane to hit the continental United States in recorded history—a grim statistic that remains 50 years later.

In 1969 however, weather satellites were still relatively new and limited in their capabilities. Indeed, the first successful weather satellite launched into orbit only nine years before Camille. But it was a big step, as it began the era of space-based weather monitoring and prediction.

A New Era

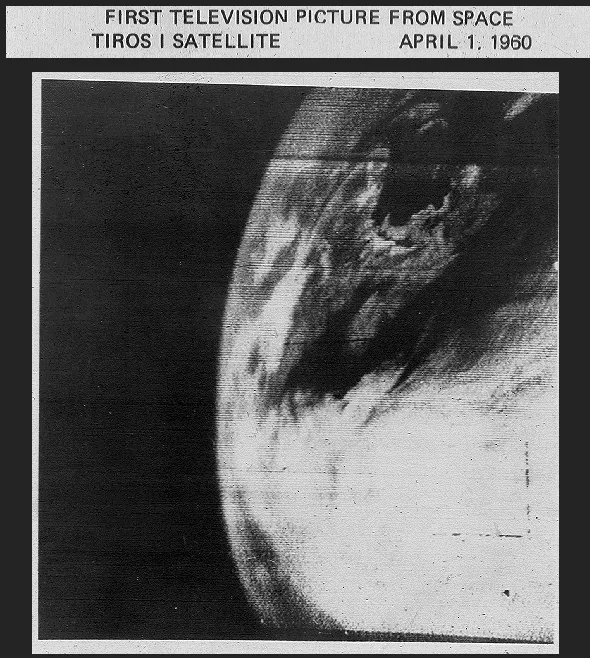

The Television Infra-Red Observation Satellite (TIROS-1) consisted of two television cameras housed in a 270-lb satellite. TIROS-1 launched on April 1, 1960, and it was the world’s first satellite that monitored the Earth's cloud cover and weather patterns. Its first image was a fuzzy picture of thick bands and clusters of clouds over the United States. Though TIROS-1 functioned for just 78 days, it provided groundbreaking views of our planet.

TIROS-1 saw the clouds from space over New England and Eastern Canada on April 1, 1960. Credit: NASA

Over the next few years, scientists at NASA, along with NOAA’s predecessor, the Environmental Science Services Administration (ESSA), designed, built and launched multiple TIROS missions, each carrying increasingly advanced technology. TIROS-3 photographed many tropical systems during the 1961 hurricane season and is credited as being the first satellite to discover a large tropical cyclone, Hurricane Esther.

Satellites as Hurricane Hunters

The Nimbus satellites were the second generation of U.S. weather satellites. Nimbus—Latin for “rain cloud” or “storm cloud”—was a series of seven missions that started with the launch of Nimbus-1 in 1964. This generation provided the first global images of clouds and weather systems, giving a much better view of tropical systems around the world.

Nimbus-3 captured this image of Hurricane Camille in the Gulf of Mexico.

By the time Camille was spinning its way across the Atlantic, Nimbus-3 was keeping an eye on it from polar orbit. Nimbus-3 was a major leap above the TIROS series and earlier Nimbus satellites. It had sensors that were able to detect the temperature of the air and ocean and also measured solar radiation above the atmosphere.

Five years after Camille, the second prototype geostationary satellite, the Synchronous Meteorological Satellite (SMS-1), launched. Just one year later in 1975, the SMS series of satellites would become the first Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites (GOES) in orbit with the launch of GOES-1.

These, along with NOAA’s series of polar-orbiting operational environmental satellites (POES), became the standard in weather satellite technology for the decades to come.

Today’s Space-based Fleet

In 2016, came the next generation of environmental observation satellites that significantly improved tropical cyclone forecasting and severe weather prediction. The GOES-R Series began when the first of its satellites, GOES-R, blasted off on November 19th of that year.

Renamed GOES-16 when it reached orbit, this satellite brings an array of new sensors—including the Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI) and the Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM)—which scientists use to get a better sense of storm intensification and thunderstorm severity.

With these instruments, GOES-16 gave unprecedented views of 2017’s Hurricane Harvey —the first major hurricane to hit the U.S. after this new generation launched. The following year, GOES-17 joined GOES-16 in orbit, bringing a more complete picture of tropical systems that threaten the central and eastern Pacific.

Another satellite, the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (Suomi NPP) brought even more advancements, including the capability of detecting power outages after storms with its Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) instrument. In fact, VIIRS’s Day-Night band helped locate areas of significant damage to the power grids from Hurricanes Sandy and Maria. This allowed scientists and first responders to compare before-and-after images of city lights to determine the hardest-hit areas.

The Suomi NPP satellite generated this before-and-after Hurricane Maria image of visible lights in Puerto Rico.

Then in 2018, the first operational satellite in NOAA’s new Joint Polar Satellite System (JPSS—a collaborative program between NOAA and its acquisition agent, NASA) became operational. JPSS-1, now NOAA-20, has five advanced, highly-sensitive instruments, similar to those currently being successfully flown onboard Suomi NPP.

Looking Ahead

As innovation in satellite technology continues, NOAA will improve its understanding and prediction of Earth’s weather and climate. NOAA plans to regularly add to its fleet of advanced geostationary and polar-orbiting satellites, while its latest joint mission, COSMIC-2 , will be another critical source of weather information when declared operational in 2020.

These satellites will be an integral part of a myriad of NOAA systems tracking and predicting hurricanes and tropical storms that threaten the U.S. down the road—especially if any more massive storms like Camille head our way.

They will all play a role in NOAA’s mission, as Neil Jacobs, Ph.D., acting NOAA administrator, said: “NOAA will continue to deliver the information that the public depends on before, during and after any storms throughout the hurricane season. Armed with our next-generation satellites, sophisticated weather models, hurricane hunter aircraft, and the expertise of our forecasters, we are prepared to keep communities informed to help save lives and livelihoods.â€