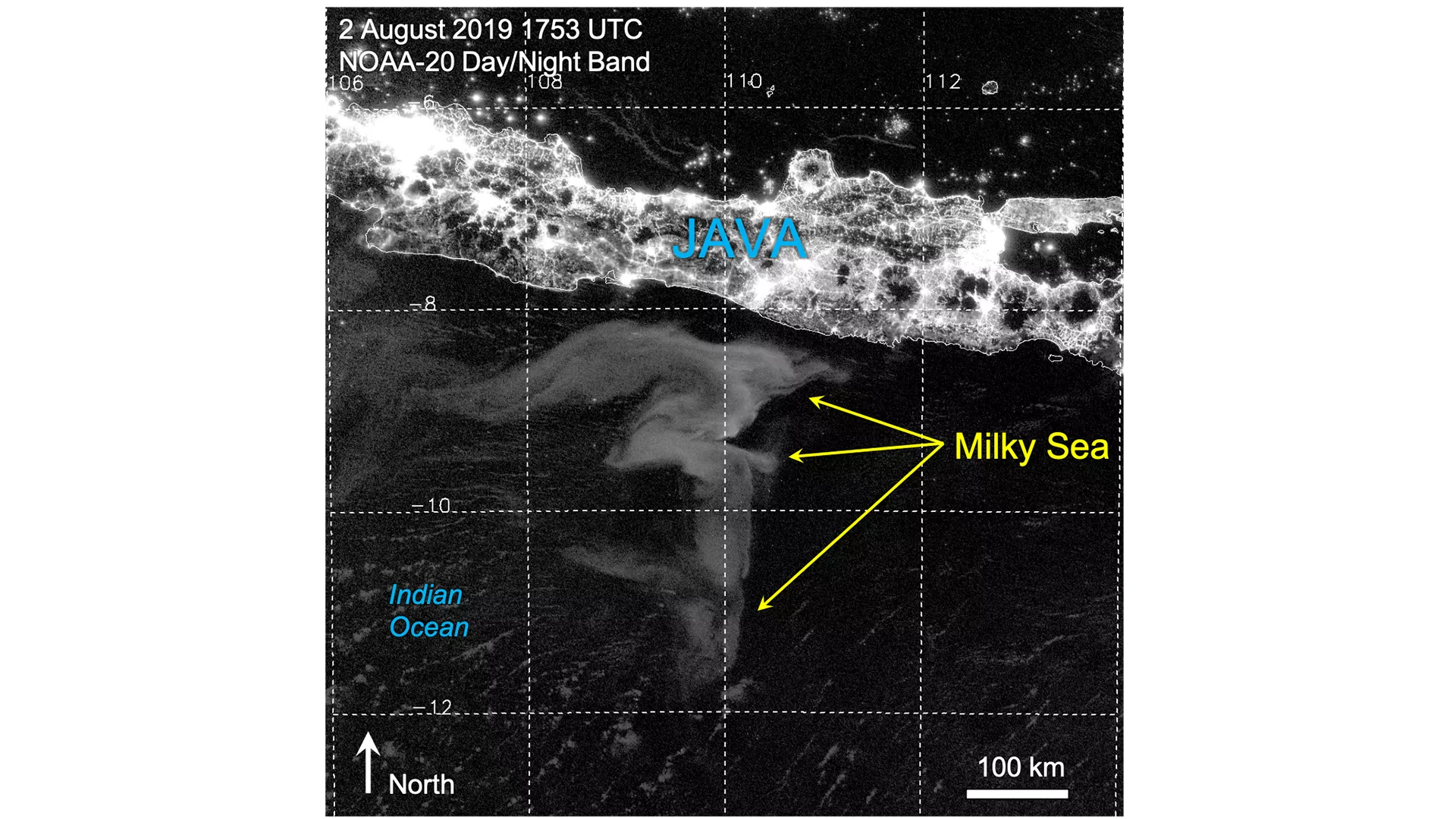

A recent study led by the Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere (CIRA), a NOAA partner located at Colorado State University in Ft. Collins. Co., found that satellites from NOAA’s Joint Polar Satellite System (JPSS) can detect a fascinating nocturnal phenomenon called “milky seas” from their perch about 500 miles up.

Milky seas are a rare form of marine bioluminescence thought to be caused by chemical reactions in certain kinds of luminous bacteria, where the nighttime ocean surface produces a widespread, uniform and steady whitish glow. Mariners across the centuries have compared their brightness to a daylit snowfield that extends to all horizons beneath the dark night skies.

Encountered most often in remote waters of the northwest Indian Ocean and the Maritime Continent, milky seas have eluded rigorous scientific inquiry, and thus little is known

about their composition, formation mechanism, and role within the marine ecosystem. The Day/Night Band (DNB), a new-generation spaceborne low-light imager included on the NOAA-20 and Suomi-NPP satellites, held potential to detect milky seas, but until this study the capability had yet to be demonstrated.

During their research, the scientists identified 12 examples of DNB-detected milky seas based on a multi-year (2012–2021) survey. These massive bodies of glowing ocean, sometimes exceeding 100,000 km2 in surface area, persisted for days to weeks, drifting within doldrums amid the prevailing sea-surface currents and aligning with narrow ranges of sea-surface temperature and marine biomass in a way that suggests water mass isolation. Their analysis offers critical new clues to understanding milky sea environments and formation mechanisms.

These results show how spaceborne assets like JPSS satellites can now help guide research vessels toward active milky seas to learn more about them.